British archaeologist Howard Carter had already spent years exploring the Valley of the Kings, an area on the outskirts of the ancient city of Thebes (modern Luxor), by the time he was hired by the wealthy aristocrat Lord Carnarvon to lead a new expedition. Lord Carnarvon, a keen Egyptologist, had heard about Carter’s belief that the ancient tomb of a pharaoh called Tutankhamun might still lie undiscovered. Whilst many others believed that anything of any worth had already been discovered in the Valley of the Kings, Lord Carnarvon placed his faith and a considerable sum of money in Carter’s theory and offered to fund a new search for the tomb.

After five years, the expedition had achieved very little. Frustrated by the lack of progress, Lord Carnarvon was about to put an end to the search when Carter pointed out that the ground beneath some ancient workers’ huts had not been excavated. On 4 November 1922, Carter and his team found the first stone step leading down to the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Three weeks later, after further excavation, Carter and Lord Carnarvon made their way through the entrance tunnel leading to a sealed doorway. Plastered and sealed by ancient priests, it appeared that the entrance to the tomb was intact, which suggested that whatever lay beyond the doorway would be undisturbed. Carter made a small hole in the sealed doorway and, using a candle to peer inside, looked into the tomb. Impatiently, Lord Carnarvon asked if he could see anything, to which a stunned Carter could only reply, ‘Yes, wonderful things’.

Hidden for more than 3,000 years, Tutankhamun’s tomb was remarkably intact. Comprising four chambers, the tomb was filled with thousands of objects.

The discovery made headlines around the world and sparked a huge interest in Egyptology, now often referred to as ‘Tut-mania’.

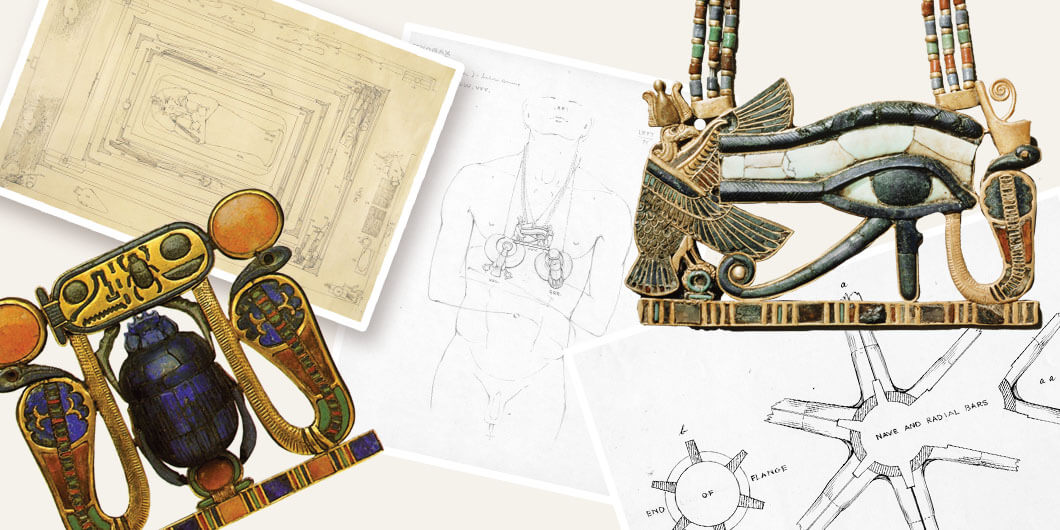

It would take more than ten years to excavate, catalogue and preserve all the objects. Although people tend to think about all the glittering artefacts found within the tomb, such as jewellery, chariots and gilded statues, ordinary, everyday objects that it was believed Tutankhamun would need in the afterlife also filled the chambers. Amongst the items found were clothing, games, food, weapons, model boats, musical instruments and even bouquets of leaves that had remained intact, dried out by the arid desert air. Continuing to be a source of great intrigue and fascination, these miraculously preserved objects give a fascinating glimpse back to life in Egypt 3,000 years ago.

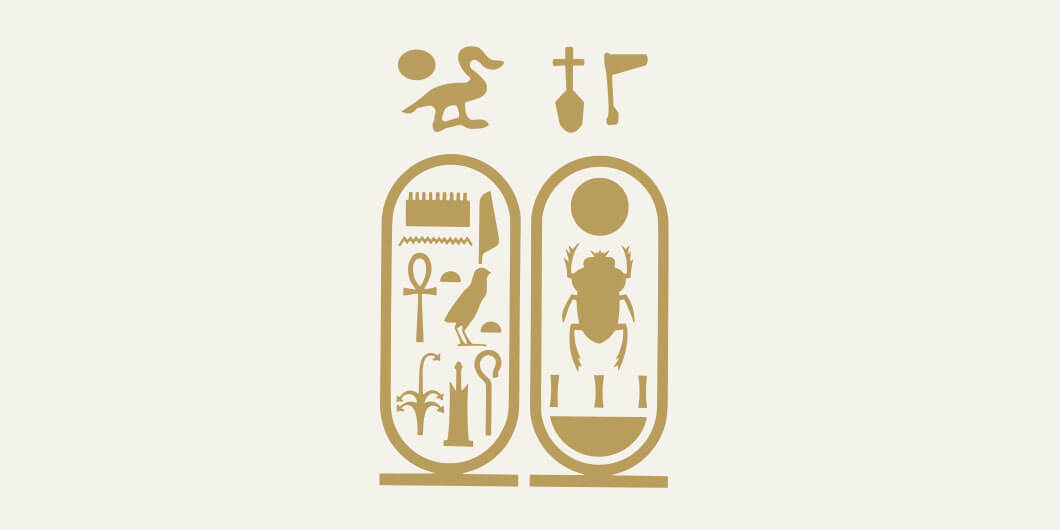

The most famous artefact found within the tomb was Tutankhamun’s iconic gold burial mask. Made from 22 pounds of gold and adorned with semi-precious stones, the mask has become synonymous with the ancient pharaoh. It was this artefact that product designer Laura Clancy decided to use as the focus of the reverse design for The 100th Anniversary of The Discovery of Tutankhamun’s Tomb UK £5 Coin. The design shows the mask in a three-quarter profile, which enhances Tutankhamun’s regal status. Inspired by a pattern found on the mask, detailing appears around the edge of the design, whilst the radiating lines in the background mirror the stripes on the mask.

Beginning in the 1960s, many of the artefacts found within Tutankhamun’s tomb toured the world, where people queued for hours to see these famous objects. Tutankhamun’s treasures will no longer travel, and a new permanent home is to open in Egypt in the coming months. The Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza will house more than 50,000 antiquities from ancient Egypt, including the complete Tutankhamun collection, and many of these pieces will be on display for the first time. Preserved for future generations to enjoy, it will ensure that Tutankhamun’s legacy lives on.

Be Inspired

Behind the Design

FIND OUT MORE