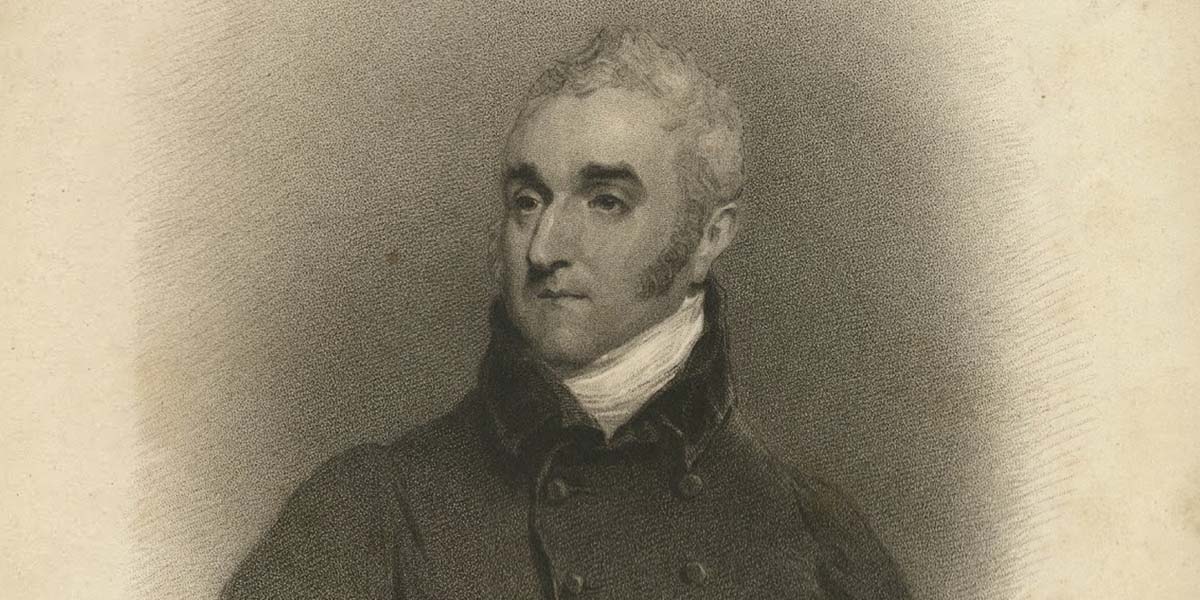

The 1818 crown features one of the most beautiful coin designs in British numismatics. Benedetto Pistrucci is rightly acclaimed as an engraver of extraordinary skill, but it was William Wellesley Pole, Master of the Mint at the time, whose vision of the crown was a quest for numismatic perfection. Time and again, in letters to James Morrison, his hard-working, much-put-upon deputy, Pole uses the word ‘perfect’ to define how The Royal Mint should approach producing the crown.

An Unknown Artist

In 1815, Pistrucci was unknown as an artist in Britain yet within a year, Pole had given him the most prestigious job any numismatic artist could wish for – preparing the coinage portrait of a reigning monarch. Even if the most agreeable of individuals had been promoted so rapidly, it would have been hard for the existing team of engravers to accept. Pistrucci compounded the situation from the start by being unyielding and aggressively self-interested.

An Iconic Design

Work on recreating St George and the dragon for a crown piece began in earnest in March 1817, giving Pistrucci the opportunity to return to the motif he had designed for the newly revived Sovereign and perfect it further. Some notable changes appeared, including swapping St George’s spear for a sword, but this might have been for technical rather than artistic reasons, given the crown’s large size.

The process by which these revisions were made is not always clear but we know Pole regularly consulted people outside The Royal Mint on matters of design. When he needed advice, he turned to Sir Joseph Banks and Dominique Vivant Denon. One of the key figures of the art world in France at the end of the Ancien Régime, Denon was a draftsman, engraver, author, diplomat and Director General of Museums, including the Napoleon Museum, which is known today as the Louvre.

With so many details, it wasn’t until spring 1818 that William Wellesley Pole sought the view of the Prince Regent, who declared himself happy with Pistrucci’s work, especially the portrait of his father, George III.

Production Practicalities

If Pole thought resolving the designs had been difficult, he had an equally trying time when confronting the practicalities of production. The engineer George Rennie, recently arrived at Tower Hill in 1818, saw the production problems at first hand and would have been fully involved in solving them. In letters to Matthew Robinson Boulton, his old employer at the Soho Mint in Birmingham, Rennie described a situation in which Pole and Pistrucci were being wilfully heedless of practical advice. With mounting incredulity, he watched one production failure follow another.

The starting point that all pieces had to be perfect caused many difficulties and necessitated rigorous quality checks, resulting in more than 500 pieces that were struck from a cracked die being rejected. Through all this, Rennie complained of Pole and Pistrucci’s ignorance and unwillingness to consider alterations.

He said of Pistrucci:

“It is impossible to have common patience to see a person so blind to the interests of the whole community as to sacrifice all to his own selfish principles.”

Part of the quality control process apparently involved every piece being presented to Pistrucci for him to examine. If this claim is true, he would have personally examined more than 150,000 coins in 1818 alone. Whilst this is not impossible, what was described as ‘Pistrucci’s ordeal’ seems unlikely.

The greatest difficulty appears to have been caused by producing a coin with a raised-lettered edge on a coining press designed to use shouldered dies and collars. This meant the raised inscription could not be rolled in as it had been in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries because subsequently striking the coins in a collar would have obliterated the inscription. A set of more complex challenges therefore presented themselves, with the solution being to use a split collar that contained the inscription.

The Great and the Good

The design was finally approved on 14 September 1818, with the first coins appearing a month later. Wrapped in paper for distribution to London bankers, they were to be regarded as works of art and handled carefully. At Pole’s request, almost 250 pieces were sent to members of the establishment, a lengthy list of the great and the good that included the Prince Regent and the queen, the Directors of the Bank of England, Pole’s sister-in-law, the Duchess of Wellington and the Archbishop of Canterbury. In some cases, this meant sending coins overseas, such as the specimens that Pole’s son-in-law, the diplomat Charles Bagot, received in Washington DC.

Mixed Reviews

Considering Pole prepared a press release prior to issue and his initials also feature on the coin, sending specimens to prominent figures appears to have been part of a calculated publicity campaign. However, despite Pole’s efforts to manipulate the media, the press quietly savaged the coin. The size of Pistrucci’s name under the bust of George III, almost certainly Pole’s idea, was perceived to indicate the arrogance of the artist and provoked hostility. Any positive reporting, such as The Times quoting Denon’s opinion that the coin was the handsomest in Europe, was accompanied by a lengthy list of criticisms.

Different Talents

Despite these contemporary press reports, the coin has assumed its rightful place as a numismatic classic. Produced during a period of huge change at The Royal Mint, the crown piece of 1818 was a key part of the technical innovations taking place at the time. It is more than just a beautiful coin, it is an expression of its time, of neoclassical influences and of the very different talents of two men, Pole and Pistrucci, coming together and creating something exceptional.

Modernising a Masterpiece

The 1818 crown features a Latin edge inscription, ‘DECUS ET TUTAMEN ANNO REGNI LVIII’, which translates as ‘An Ornament and a Safeguard in the 58th Year of the Reign’. This phrase is commonly found on British coins and indicates that it was minted in the 58th year of George III’s reign. This has been skilfully updated on the modern recreation of Pistrucci’s classic design to reflect the year of reign for the current monarch, King Charles III.

Discover Great Engravers

THE LIFE OF THOMAS SIMON

Discover Thomas Simon

THOMAS SIMON’S PETITION CROWN – BEHIND THE DESIGN

An Appeal Through Artistry

A PROLIFIC ARTIST

Discover William Wyon

A COIN OF RARE BEAUTY

Una and the Lion