Chris Barker, Information and Research Manager at The Royal Mint Museum, explores the journey of Britain’s coinage, from the inclusion of heraldic designs to those that feature more naturalistic designs, including fauna and flora.

Throughout history, coin designers and artists have been drawn towards heraldic devices in relation to Britain’s coinage. Rather than naturalistic forms, which have only briefly been explored, Shields and Arms have often been the chosen symbols used to represent the nation. For centuries, despite being interspersed with the occasional heraldic animal or sprig of greenery, Western coinage design has followed a rather formulaic, heraldic route, but it has not always been this way.

Ancient coin designers captured the natural world in all its glory, and it was the Greek city states that did it best. Whether they featured symbols of the gods, such as the owl associated with Athena, a goddess of war, handicraft and practical reason, or native animals of a region, as displayed on the coins of Eretria or Akragas, these vivid and beautifully executed works of art are instantly recognisable. Such forms, and the skill necessary to execute them, largely disappeared from the canon of coinage design after the end of the Roman era, and it was not until the Irish Free State coinage in the 1920s that the same spirit of these early Greek pieces was recaptured.

Needing an expression of the new state’s identity on its coinage, it was towards Ireland’s well-established agriculture sector and its proud history of animal husbandry that the recently established Irish Coinage Committee turned for inspiration. Led by the famed poet W. B. Yeats, the Committee had to choose a set of designs from the 66 submitted by the seven artists invited to take part. Percy Metcalfe’s distinctive series of stylised animal designs were a firm favourite amongst the judges, who felt his work far exceeded the decorative quality of the other pieces.

As Yeats himself put it, ‘What better symbols could we find for this horse-riding, salmon-fishing, cattle-raising country?’

Receiving enthusiastic praise from the British press, the designs were described as ‘the most beautiful coinage in the modern world’ by the Manchester Guardian and, following the death of George V, Britain was presented with an opportunity to follow in Ireland’s footsteps regarding its coinage. Keen to design a more modern coinage, there was a real desire to break free from the confines of heraldic tradition and embrace, in part, the flora and fauna of the nation. However, it would prove to be a tough brief, particularly when viewed through the narrow lens of royal animals. The swan, sturgeon and eagle all fell by the wayside, but one design that did stick was the delightful wren, which was the work of artist Harold Wilson Parker. Appearing on the farthing until the 1950s, when it ceased to be struck, the coin became a favourite with the British public and many still fondly remember using them.

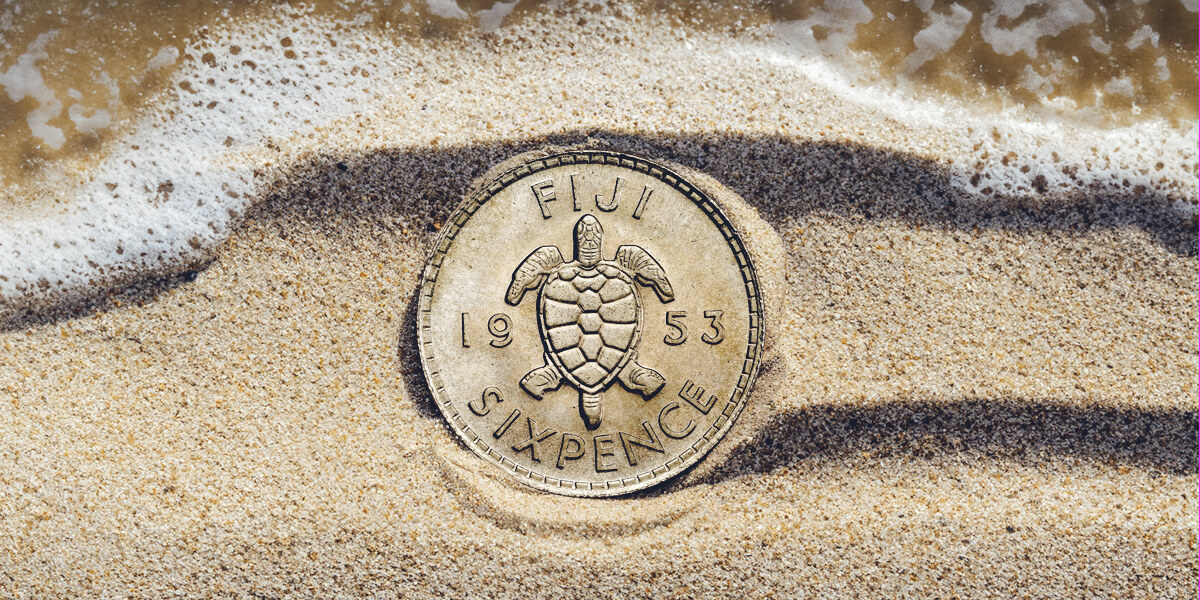

Despite the ambitions of the time, the wren proved to be one of the few heraldic departures for the new coinage designs issued in 1937. Many of the pieces were the work of artist George Kruger Gray and were the perfect example of modern, heraldic coin design. Innovation in terms of the subject matter was few and far between on British coinage in the decades that followed, but other countries embraced the use of native animals and flora. The distinctive and iconic appearance of some of these animals, such as caribou from Canada or the turtles found in the waters of Fiji, lent themselves to become part of strong, aesthetically pleasing designs that could instantly be associated with their country of origin.

Australia’s rich, distinctive wildlife provided the perfect subject matter, and the country’s decimalisation programme in 1966 presented the perfect opportunity to design a full suite of coin designs on the subject. Silversmith Stuart Devlin was Metcalfe’s spiritual successor, adding a modern aesthetic to the designs and impressing the judges with the way he was able to inject a sense of movement into his modelling of the animals. Devlin felt that the designs represented a more sophisticated and grown-up nation that distanced itself from the ‘national advertising’ of previous designs. Instead, he aimed for it to be a ‘reflection’ of Australia’s ‘cultural spirit’.

The new definitive designs created for coins of His Majesty King Charles III therefore continue a long tradition that stretches back all the way to ancient Greece. A watershed moment for British coinage, these new designs, more or less for the first time, step away from the heraldry that has dominated for centuries. The timing of this could not be more apt, as coinage designs have often, in one way or another, represented the era in which they were made. For a king who has dedicated much of his life towards the conservation of the natural world, they represent a lifetime’s work. Equally, in an era when nature and wildlife are increasingly under threat from climate change, they are a reminder of the beauty of the natural world and what is at stake.

We Recommend

1971 Britain’s First Decimal Coin Set in Blue Wallet

A great nostalgic gift

Price: £10.00

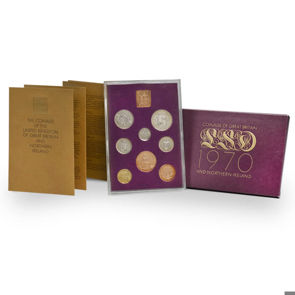

1970 Pre Decimal UK Proof Set

One of the first modern Proof sets to be produced by The Royal Mint

Price: £60.00

The Modern Monarchs Starter Set

Includes King Charles III Coronation Medal

Price: £95.00

The Three Carolean Kings Silver Three-Coin Set

Limited Edition 100

Price: £1,250.00

BE INSPIRED

Moments of Change

Read More

By Royal Approval: The United Kingdom’s New Definitive Coins

Read More

THE WORK AND INTERESTS OF HIS MAJESTY KING CHARLES III

Discover More